Minangkabau decorative motifs are integrally connected to adat. Historically, scholars—especially anthropologists—have put undue emphasis on the cultural meanings conveyed in decorative motifs or described these connections too narrowly. This criticism is good to keep in mind in any discussion of what a motif “means” since no culture is monolithic and many people that identify as sharing a similar culture will read a different meaning into the same symbol. The close relationship between adat and the decorative motifs Minangkabau weavers used in these textiles makes this sort of reading reasonable in this instance, however, because instead of being imposed from the outside the connection between motif and meaning is explicitly expressed among Minangkabau people.

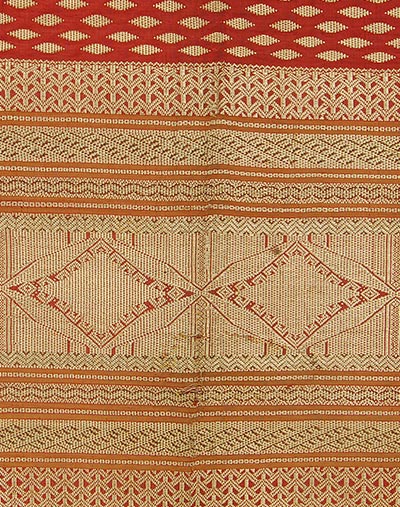

Minangkabau people have used many of the motifs woven into these textiles for thousands of years. Some of the oldest ones have been found carved on rocks in Limo Puluah Koto regency. Different weavers represent them in different ways, but the most popular ones are readily identifiable. Some of the most popular motifs are: balah kacang (split peanut), are barantai (chain), kaluak paku (fern tendril), itiak pulang patang (ducks go home in the afternoon), pucuak rabuang (bamboo shoot), batang pinang (trunk of the areca palm). Each of these designs is represented in several different ways on the textiles in this collection.

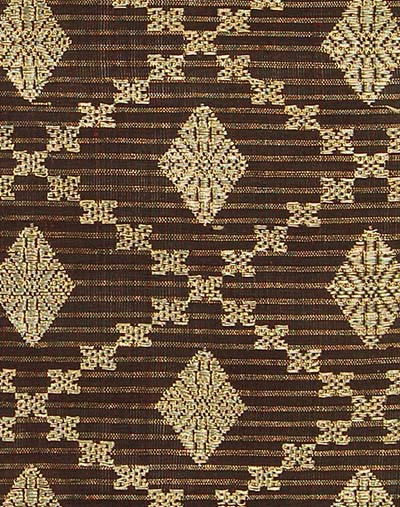

Balah kacang

(split peanut)

This motif teaches the lesson that when it comes to sharing, portions must divided equally the same way a peanut is naturally divided into equal sections.

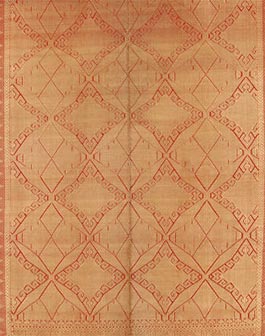

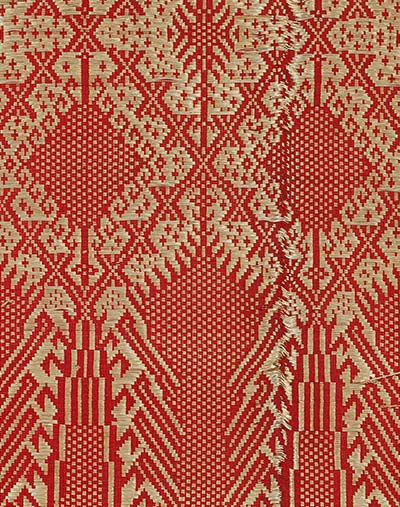

Barantai

(chain)

This is a pattern of intersecting diagonal lines of x’s that symbolizes community involvement. In the same way that a single chain link is useless but a set is strong, each individual in the village is better off when everyone works together.

Kaluak paku

(fern tendril)

This is a spiral design that refers to a chief’s responsibilities to his children, his sister’s children, and his community. This motif is particularly hard to make on a textile because of the difficulty inherent in trying to weave a rounded pattern.

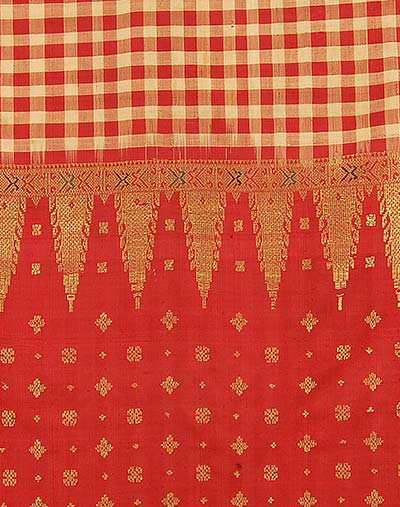

Batang pinang

(trunk of the areca palm)

This is a narrow warp stripe that is likened to the areca palm and used to explain the ideal qualities of a Minangkabau mother. Like the trunk of this palm tree, she has integrity and she and her children stay close and grow together.

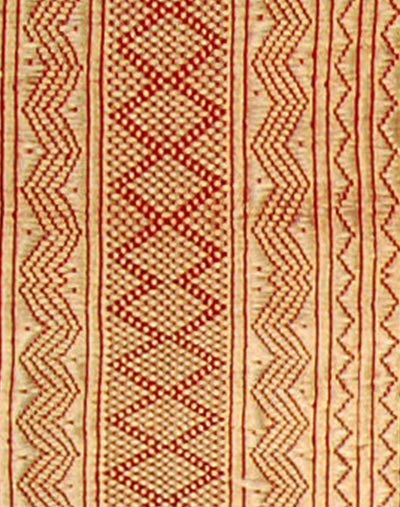

Itiak pulang patang

(ducks go home in the afternoon)

This appears to be one of the earliest indigenous motifs in the area. It appears on stone megaliths in the region that are 4,000-5,000 years old. The name refers to the way ducks travel together in lines and is used to demonstrate the way a person should follow adat closely.

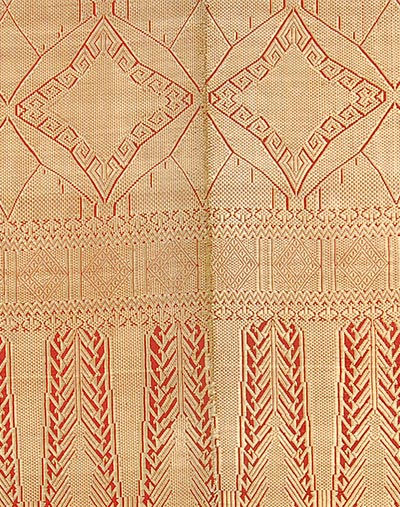

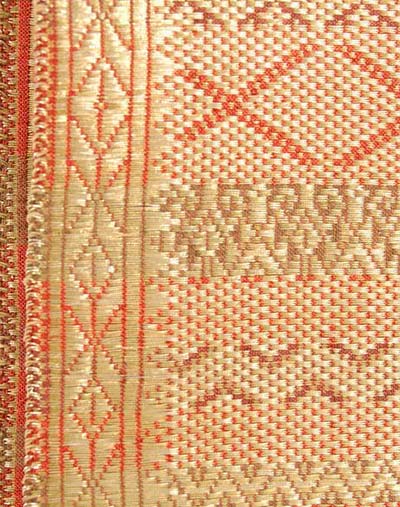

Pucuak rabuang

(bamboo shoot)

This is interpreted several ways, all relating to the roles men play in Minangkabau culture. The first is that it symbolizes the three roles men play that are the most important to Minangkabau cultural survival: the chief, the religious leader, and the intellectual. A row of these triangles placed side-by-side (plain or embellished) symbolize the way men in these roles act as the “fence” of the community.

This motif can also symbolize the way a young man should behave: that he should go quickly and directly to accomplish his goals and then become humble and remember his beginnings, the way a bamboo shoot grows up quickly and then bends over as it ages.

References

Achijadi, Judi. Floating Threads: Indonesian Songket and Similar Weaving Traditions. Indonesia: BAB Publishing, 2016.

Eiko Kusuma Collection. Weaving, Dyeing and Embroidery: Diversity in Sumatran Textiles from Eiko Kusuma Collection. Japan: Fukuoka Art Museum, 1999.

Summerfield, Anne and John. Walk in Splendor: Ceremonial Dress and the Minangkabau. Los Angeles: UCLA Flower Museum of Cultural History, 1999.

Summerfield, Anne and John. Fabled Cloths of Minangkabau. Santa Barbara, CA: Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 1991.